I was a 10-year old kid when my mom took us to Portland, Oregon, to visit her Aunt Edna. On the mantle of Aunt Edna’s fireplace I noticed a framed sepia toned picture of a young flyer with hand-tinted rosy cheeks. I did not recognize him.

“Who’s the soldier in the picture over your fireplace, Aunt Edna?”

“That’s my boy. His name was Kenneth. He was your cousin…Second cousin. Back when we had the farm, when he was a teenager, he learned how to fly because he wanted to be a crop-duster. He was good. And then my boy made a name for himself barnstorming up and down the Willamette Valley.” She paused. “Then the First World War came. He was an ace. He shot down nine German planes. He was shot down over France.”

When she told this small boy about her handsome son this small boy could see that it still pained her all these years later to repeat the story, as if she’d been handed the dreaded telegram yesterday. She leaned against the fireplace mantle and studied her boy’s face for the longest moment. And then turned to make us supper.

When I was a young man, while visiting Washington, D.C. I wandered into the National Gallery of Art-East Building to explore their contemporary art collection.

There were two touring exhibitions I was excited to see.

First, a traveling show of the works of Auguste Rodin.

It was the second exhibition, by an artist unknown to me, Kathe Kollwitz, that left me speechless, an exhibition of sculptures, lithographs, etchings, woodcuts and prints. I learned Kollwitz had lived in Berlin, she was a Professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts until the Nazis forced her to resign. Kollwitz’ beloved son, Peter, had also died in the First World War. She knew the grief that gripped my aunt more than half a century after the loss of her beloved boy. In “The Parents”, a woodcut rendered by Kollwitz in 1923 she expresses the most powerful scream of grief I’ve ever seen.

I fell in love with the dark haunting work of this brilliant artist who created such powerful visual statements she was branded a “degenerate artist” by the Nazis. Kollwitz remains the most eloquent, compelling social protest artist I’d ever seen. She turned her grief and rage and pain into universal timeless art, humanist testaments that will forever resonate long after the fascists who sought to silence her turned to ash and dust.

In her youth she adopted a naturalistic style, drawing forms in a realistic manner with detailed line work. As she matured her work grew simpler, more expressive and more arresting. Each new piece was a bold assertion, a compelling statement rather than a mere illustration one could pass over and dismiss.

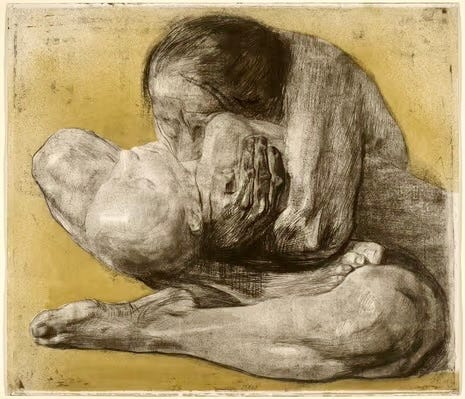

Below is “Woman with Dead Child”, an unforgettable image imagining the unimaginable. For this ink slinger the figure of this mother burying her face in her child’s limp body, perhaps kissing the child’s stilled heart rivals Michaelangelo’s Pieta for it’s personificaton of grief. The piece rocks with grief. And she rendered this masterwork before her own son died in war fifteen eyars later. How often do we see such scenes repeated by the hundreds and thousands in the madness of modern war around the world today? In Gaza, in Israel, in Aleppo, in the Sudan, in Somalia, in Libya and on and on?

Of the many sculptures sculpted by Kollwitz that I saw at the National Gallery, on that day, more than 40-years ago, one stays fresh in my memory. It was among the most moving sculptures I had ever seen. Or will ever see. Called “Tower of Mothers” Kollwitz depicted a circle of mothers, arms locked, defying the agents of war to take their children from them. It was modest in size, smaller than a cookie jar, set on a low pedestal, so that the viewer could circle it and gaze down into the maelstrom of jostling women and see the children within.

In this work a circle of mothers are united in resistance against the oceanic forces of history, struggling desperately to hold off the encircling forces of death, their innocent children behind them, clutching their skirts and arms. As it has always been. Kollwitz renders the primal truth of war that Fascists brand treasonous and the barbaric despise: Children will die, inncoents will perish. Troubled by the popular power of her work the Gestapo visited her and urged Kollwitz to still her hand. She refused, knowing her popularity among the people in Germany would protect her. Kollwitz remained untouched. In 1943 her home was hit during a bombing raid and much of her art and her printing plates were destroyed. After fleeing Berlin Kollwitz died in Moritzburg, Germany in 1945.

References:

“Kathe Kollwitz”, Elizabeth Prelinger, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., bit.ly/3FSRBZx

“The Kathe Kollwitz Museum” in Berlin, https://www.kaethe-kollwitz.berlin/

These few renderings bring me to tears. I can only imagine the power in viewing such…

Grief remains with us always and if we do not find a way to reconcile with it, with new meaning, it can overwhelm us.

Thank you for sharing with us.